EAP Publications | Virtual Library | Magazine Rack | Search | What's new

Sweet corn is a staple of the Massachusetts agricultural economy. Grown exclusively for the fresh market, it accounts for about 40% of the vegetable cash receipts in the state. Sweet corn receives high amounts of insecticide compared with most other Massachusetts vegetables. The Massachusetts Sweet Corn IPM Program, initiated in 1985, aids cooperating growers in monitoring and suppressing sweet corn pests with the minimum necessary pesticide treatments.

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) uses a variety of techniques--crop rotation, tillage, biological and chemical controls, for example--to manage crop pests. Knowledge of the crop, its pests and their natural enemies, along with regular monitoring of pest populations, is essential to this integrated approach. So is the establishment of rational "action thresholds," which determine when to undertake a pest management action based on pest population levels and the economics of control.

IPM was developed as a response to problems associated with scheduled chemical treatments: environmental contamination, disruption of natural enemies, pesticide resistance, and concerns about residues in food. In general, contemporary IPM programs are in a "pesticide management" phase in which chemical control remains the principle control, but significant cutbacks are possible through the use of pest monitoring and action thresholds for control.

Massachusetts supports IPM programs for several commodities with the objective of increasing profitability of agriculture, while protecting the state's environment by reducing unnecessary pesticide applications.

Current information on specific sweet corn insecticides and herbicides, cultural controls, and cultivars is available in the most recent New England Vegetable Production Recommendations.

The Massachusetts Sweet Corn IPM Program uses the following criteria for pest management decision making:

Pheromone traps are our primary technique for monitoring common pests. Black-light traps are used in other states, but they have several disadvantages, namely, they attract many insects unrelated to corn, and they require a power source. Pheromone traps, in contrast, are specific to the insects of interest, and they are relatively inexpensive and easy to maintain.

Pheromones are chemical scents that animals use to communicate with others of their species. The best known are insect sex pheromones. We use synthetic pheromone lures, which mimic the scent of the female moth, to attract male moths of that particular species. A well-designed trap, if properly placed, will capture these males so that their abundance may be monitored. Reducing pest numbers by trapping large numbers of moths is not feasible for most species, and is effective only under very special conditions. The Massachusetts Sweet Corn IPM Program uses traps for monitoring purposes only.

Monitoring with pheromone traps is useful because pest pressure varies from farm to farm and over time. Knowledge of when and where adult pests are active and abundant provides a sensitive early-warning system to initiate field sampling and/or control. Migrant pests, such as corn earworm, may arrive in New England from early June to August, depending on weather patterns. Knowing whether or not pests are present allows the grower to eliminate unnecessary pesticide applications or time consuming sampling, and gives advance warning to protect crops when moth flights are first detected.

Traps catch only adult male moths. Adult moths do not damage the crop; only the larvae do. Therefore, we cannot simply count moth numbers in the traps and ignore other factors, such as temperature and crop growth stage. Because the relationship between trap numbers and amount of damage can vary, temperature and growth stage should be considered in control decisions.

Successful pheromone trapping of sweet corn pests requires:

Lures: Pheromone lures differ among manufacturers, and some brands are definitely better than others. Sources are listed in this pamphlet, as well as the types of lures used in the Massachusetts Sweet Corn IPM Program. Most lures need to be replaced every two weeks. For a field season of 20 weeks, 10 lures will be needed per trap.

Traps: Traps also differ from source to source. The appropriate type for each species is shown below under the pest descriptions. Sticky traps are messy to use and require frequent replacement. They may fill up with moths, making the trap useless for monitoring pest populations. The traps we recommend are durable (lasting two or more years), and will continue to catch target moths even when these are present in abundance.

Placement: Proper placement of traps is critical, but sometimes overlooked. Choice of the right habitat and appropriate height from the ground are most important. For example, fall armyworm traps should be placed in whorl corn, at 3 1/2 feet height. When corn is near tassel stage, the traps should be moved to a younger planting

Monitoring: Examine traps at least once a week, if possible on the same day of the week each time. Empty the traps at each visit, and immediately record number of moths captured. Especially when large numbers of moths are captured, dispose of specimens away from the trap site. Since moths fly at night, the trap catch will reflect the number of nights since the last collection.

Non-target insects are sometimes captured in pheromone traps. Therefore, it is important to familiarize yourself with the pest insect you are trying to trap, to confirm that the trap has captured the target insect.

Lure replacement: Replace lures every two weeks. Use metal binder clips (tied onto string of Heliothistrap,orclipped into Multipher cage) to make replacement easier. Wear a different glove to handle each different lure type, including the two ECB strains. Place old pheromone lures and other contaminated material in a ziplock bag and dispose of away from field sites. Do not leave old lures or gloves near the trap site since they will attract moths away from the trap, distorting pest counts. Careful handling of pheromones is essential, since the quantities involved are measured in nanograms (billionths of a gram, or 1/30-billionth of an ounce), and many moths are repelled by the pheromones of other species. It should be clear that contamination or confusion of one lure with another could be disastrous in terms of monitoring.

Sources for pheromone traps and lures

There may be other sources. We are not endorsing these companies, but listing them as possible sources because growers frequently ask for this information.

Especially following high pheromone trap catches for fall armyworm or European corn borer, it is important to scout sweet corn blocks for larval damage. Our thresholds are based on numbers of plants infested, not on numbers of larvae per plant. Thus, a 15% infestation means that, on average, 15 out of 100 plants checked will show live larvae.

We recommend inspecting at least 100 plants well distributed through each sampled block. Avoid prejudicing your results: Do not pick plants on the basis of damage. To ensure unbiased results, pace a predetermined number of steps, sample the nearest plant, and repeat until you cross and recross the field, preferably in a V-shaped transect.

There are two important reasons not to make treatment decisions based on the mere presence of damage. First, what looks like significant damage may not be near the threshold for treatment, and may be confined to borders or other limited areas of the block. Second, damage will be present after larvae either have left the plant to pupate or have been killed by natural enemies or previous pesticide treatments. Infestation counts must be based on percent of plants having live larvae.

Following germination, sweet corn emerges as a spike from the soil. Its leaves unfurl within a few days, initiating the whorl stage of development in which only leaves are visible. Fall armyworm and common armyworm lay their eggs preferentially on whorl-stage corn, and the larvae are easily monitored in this stage. When the whorl-stage plant is 18 to 40 inches tall, the tip of the tassel (the male flowering structure) becomes visible from above, buried in the center of the whorl. This begins the pretassel stage, which ends when the tassel is fully emerged from the whorl. Pretassel corn should be scouted for European corn borer larvae if pheromone catches indicate adult activity within the previous four weeks. Green tassel stage occurs when the tassel is fully exposed but not yet shedding pollen. By the time the tassel is shedding pollen, the silk usually has emerged from the developing ears (the female flowering structures), initiating the silk stage. Silk grows rapidly, 3 to 4 inches the first day and about 2 inches over the next four days. Silks emerge over about a week's period within a block, posing a challenge to the grower to protect new growth if earworm are present in the area. After pollen has landed on the silk and fertilized the ear, the silk dries, and kern, Is develop and swell to the milk stage, at which time the corn is ready for prompt harvest. Harvest of sweet corn follows the beginning of silk by approximately 21 days. Overall time from planting to maturity varies among cultivars from about 60 to 100 days.

The three major sweet corn insect pests in New England are European corn borer, corn earworm, and fall armyworm. All are moths or lepidoptera, with a larval stage called a caterpillar or "worm." The adults, which feed only on nectar, do not damage the crop. Adult female moths lay their eggs on or near certain plants, including sweet corn, which are food for the larvae when they hatch. The larva is the damaging stage. It feeds and grows, molts through several stages (instars), then transforms to a resting stage, the pupa. From this pupa emerges the adult.Our strategy in the Sweet Corn IPM Program is to use the adult populations as an indicator of the potential for larval infestations in the crop, supplemented in certain cases by field scouting for larval damage. The biology, damage, and monitoring methods for the major sweet corn pests are outlined below.

European corn borer (ECB) is an introduced pest and a year-round resident in New England. It feeds on a wide variety of host plants, including corn, potato, bean, pepper, beet, chrysanthemum, dahlia, gladiolus, eggplant, and as many as 200 weed species. It is the most important pest of sweet corn in Massachusetts.

ECB overwinters as a last instar larva inside corn stalks and the stems of other host plants. In the spring, the caterpillar pupates, and emerges as an adult as early as late May in Massachusetts. Mating occurs at night in grassy areas adjacent to cornfields. Females move into the crop at night, laying egg masses with 5 to 50 eggs each on the undersides of leaves. They may lay as many as 500 to 600 eggs total. Eggs hatch in about one week, depending on temperature. Small larvae feed initially in leaf axils and in the tassel, later moving to the stalk and sometimes to the corn ear.

In the eastern United States, ECB occurs as two distinct pheromone races, known as E and Z, which respond to different pheromone blends. Both occur throughout Massachusetts, requiring ECB monitoring to include a trap for each strain at each farm. Typically, both strains have two generations a year, with adult peak flights in June and again in August and September. However, a one-generation Z strain, which flies in July, occurs in Berkshire County and parts of New York State.

First generation June population) ECB larvae feed on the foliage and in the stalks and tassels. The corn plant can tolerate high levels of this damage. It is only when the larvae feed in the ears that they truly cause economic damage. For this reason, it is not necessary to apply treatments for this pest until the pretassel stage, and then only if ECB infestation exceeds 1596 of plants in a field. One or two insecticide applications are generally all that is required to control first-generation larvae in early harvested (July-maturing) sweet corn. Corn planted under clear plastic or row covers often has developing ears at the time when ECB adults are active, and for this reason may suffer higher levels of ear infestation than corn planted to bare ground.

Second-generation populations (August and September) are generally larger than the first generation, and adult moth activity extends over a longer period, often requiring more pesticide applications to late-maturing crops.

Destruction of corn stubble is important in suppressing overwintering populations of ECB. Most of the larvae are found in the lower 6 inches of cornstalks. Silage chopping and early spring plowing (no later than May 1st) help to reduce overwintering numbers.

ECB is rarely controlled in New England field corn. Sweet corn planted after or in the same area as field corn is more likely to show high ECB damage, especially if corn stubble is left in the field.

Trap type: Scentryx Heliothis trap (plastic mesh); two traps required, one each for E and Z strains.

Parts: 7-foot fence post, trap with detachable fine-mesh top and 3 tie-downs, tent stake, string or wire and binder clip for holding lure. Lure type: rubber septum (from University of Massachusetts or Trécé).

Placement: in tall grass or weeds adjacent to corn field. Trap bottom should be immediately above tallest vegetation; adjust as necessary. Lure should be hung on taut string or wire suspended across the trap opening. Two traps should be used, one each for the New York (E) and lowa (Z) strains, spaced at least 10 yards apart.

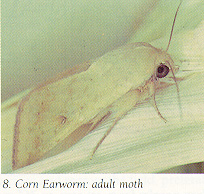

The corn earworm is one of the most destructive insect pests attacking sweet corn in North America. It is not a permanent resident in New England, but instead migrates from the South, reinfesting the Northeast each year. It may appear from late May to early August, depending on location and year-to-year variation. The heaviest infestations in Massachusetts occur late in the season and along the coast, especially the south coast, Cape Cod, and Islands.

Corn earworm is our most difficult pest to control. The migratory habits of adult corn earworms, which are very strong fliers, account for sporadic and rapid infestations. This, along with the fact that damage is generally hidden until harvest, makes monitoring using pheromone traps an essential strategy for earworm management in Massachusetts.

The female lays eggs singly on the corn plant, many of them directly on the silk. Other plants infested include tomato and beans; corn earworm is also called tomato fruitworm. The female may lay 1000 eggs. Egg hatch time is determined by temperature, occurring from 2 to 6 days after eggs are laid. If eggs are laid on the corn silk, larvae bore directly into the silk channel to the tip of the developing ear shortly after hatching. Larvae feed on the ear, usually remaining near the tip and fouling it with frass (droppings). Fully-grown larvae leave the plant to pupate 3 to 5 inches below the soil surface. Adults emerge 10 to 25 days later. In the late season, adult earworm populations are a mixture of these offspring and new migrant moths.

Once the earworm larva has entered the ear, there is no effective control. Chemical earworm control requires very good protective coverage of the ear zone at times when adult moths are active. Double-drop nozzles (see Figs. 1 and 2) offer the best spray configuration for this purpose. Recommended spray intervals for silking corn are based on pheromone trap catches and temperature. Because damage is usually restricted to the ear tips, growers may be able to market earworm-infested harvest successfully, depending on consumer preference. Corn earworm trapping specifications Trap type: Scentry® Heliothis trap (plastic mesh); Texas Heliothis trap (wire mesh) may also be used; see note under "Guidelines for Sweet Corn IPM Decision Making."

Parts: 7-foot fence post, trap with detachable fine-mesh top and 3 tie-downs, tent stake, string or wire and binder clip for holding lure. Lure type: laminated Luretape® (Hereon).

Placement: in silking corn, or in early season, the planting which is most advanced in growth. Move as necessary. Minimize interference with farm machinery by flagging with bright surveyor's tape. Bottom of trap should be 3'h feet above the ground.

Like corn earworm, fall armyworm (FAW) does not overwinter in our region, but instead migrates north from the deep South to New England. Depending on location and weather pattems, it may appear in early July, later in the season, or not at all. Highest numbers occur late in the season and near coastal areas. FAW invasions are more sporadic than those of corn earworm, making on-site monitoring important. Fall armyworm is not as important a pest as CEW or ECB, but at times may be very destructive to whorl-stage sweet corn if not suppressed.

Females lay clusters of about 150 eggs on a variety of plants including sweet corn, in which they prefer whorl-stage plants. Eggs hatch within 2 to 10 days, and larvae remain on the plant, often deep in the whorl. Their feeding produces rows of large holes in growing corn leaves, and may delay maturity or decrease overall yield. Larvae mature and pupate in the soil after about 20 days. Most adult FAW in Massachusetts are migrants rather than local offspring.

Whorl infestations of FAW do not require treatment if less than 15% of plants are infested. If whorl treatment is required, direct sprays down into the whorl with a single nozzle over each row, using a high volume of water. Silking corn may need to be protected against FAW if pheromone trap catches indicate high numbers.

Parts: 6-foot fence post, 4-part plastic trap, nopest strip, string or wire for hanging, binder clip to hold lure.

Lure type: rubber septum from Raylo.

Placement: in whorl-stage corn, trap about 3 1/2 feet high, hung on slanted post. Avoid placement which will interfere with spraying and fertilizing operations. Mark with bright flagging. Move to new whorl corn as old crop comes into tassel. Use wire to hang trap in windy sites.

No-pest step: should be replaced every six weeks. Handle with gloves; dispose of with pheromones.

Note on non-target moths: large numbers of a light-winged noctuid moth, wheat-head armyworm, are being encountered in the early season. These are not a pest of corn.

Common armyworm (CAW) produces the same type of whorl injury as fall armyworm, but unlike FAW may overwinter here and can cause damage as early as May 14 and 15). CAW is rarely an important pest in our region. The combined threshold for CAW and FAW is 15% of whorl plants damaged. Pheromone traps and lures are available; however, if you are scouting for damage, there is little to be gained by use of these traps.

This resident pest may be locally common in grassy areas of sweet corn fields, where larvae typically feed on weedy grasses before moving to whorl-stage corn plants. Stalk borers cause armyworm-like damage and often bore into the stalk, sometimes breaking it. Management consists of improving control of grassy weeds and, if necessary, spot treatment of infested patches.

This bluish-green aphid is the principle colonizing species on sweet corn, and may be especially abundant in the developing tassel and occasionally on the ear and flag leaves press sweet corn pests are broad-spectrum. Large populations produce sticky honeydew, which supports black sooty mold. This cosmetic damage may be avoided by a single insecticide treatment at green tassel stage.

Corn leaf aphid is a poor vector of Maize Dwarf Mosaic Virus, discussed below. Control of corn leaf aphid has little or no impact on the spread of this corn pathogen.

Pollinators, predators, and parasites play a beneficial role in agricultural ecosystems. At present, most of the insecticides used to suppress sweet corn pests are broad spectrum, non-selective toxins, which will kill beneficial species as well as the target pest populations. This is one of the reasons why IPM must encompass a least-is-best pesticide use strategy.

Among pollinators, honeybees visit tasselling corn in large numbers to gather pollen, even though corn itself is wind-pollinated. Certain pesticides (notably Penncap-M® ) are not registered for application during corn tassel, in order to protect pollinators.

Predators include ladybird beetles, predatory stink bugs, lacewing larvae, and ground beetles. In the sweet corn system, predators alone do not accomplish substantial control of the important pests. Parasites, especially small parasitoid wasps, may at times be important in suppressing the lepidoptera, especially European corn borer. The minute egg parasite Trichogramma is currently being investigated as a control which could be released in large numbers when pest eggs are abundant. In their adult stages, parasites are quite susceptible to most insecticides currently in use.

Maize dwarf mosaic (MDM) is the most serious sweet corn disease in Massachusetts. It has become widespread throughout the United States since its appearance in the 1960s. The disease reduces plant growth and contributes to yield loss primarily by lowering marketability of ears.

The causal agent, Maize Dwarf Mosaic Virus (MDMV), is transmitted by at least 12 species of aphids in a non-persistent manner, that is, via the mouthparts or stylets. Aphids acquire the virus within seconds while probing an infected plant in search of a suitable host plant. Aphids retain the virus on their stylets (for as long as 70 hours), and after migration transmit the virus while probing a non-infected host for feeding suitability. Aphid species in Massachusetts known to transmit MDMV are green peach aphid, potato aphid, corn leaf aphid, and English grain aphid.

The overwintering plant host of MDMV is not known in the Northeast; however it is suspected to include several grasses common to our region The virus is spread by aphids from the overwintering hosts to corn fields, primarily in mid-July, when large flights of winged aphids occur. MDM symptoms appear on the youngest leaves about a week after infection. An alternating light and dark green molding develops as narrow streaks along infected leaf veins. This mosaic pattern spreads, with an overall chlorotic or yellowish-green appearance. Infected plants are often stunted. Ears of infected plants are smaller, and kernels do not completely fill ear tips and butts. The relationship between MDMV infection and severity of symptoms is not simple. Early infection, high temperature, and cultivar susceptibility all tend to make symptoms more severe.

Control of the aphid vectors is ineffective for reducing the spread of MDMV because of the large numbers of aphids involved and the rapidity of styles-borne virus transmission. Resistant cultivars offer the best hope for minimizing MDM-related losses; see New England Vegetable Production Recommendations for a list. Use of tolerant or resistant cultivars is advised in planting late-season blocks which have had a history of MDM infection. Late-season blocks of MDM-susceptible varieties should not be planted near peach, cherry, or related trees, which are overwintering hosts of green peach aphid, or near wild rose, the overwintering host of potato aphid.

Stewart's wilt is a sweet corn disease caused by a bacterium, which overwinters in corn flea beetles and infects corn seedlings when the beetles feed on them in the early season. The beetle is 1/1 6-inch long, black, and capable of jumping vigorously when disturbed. Stewart's wilt is uncommon in Massachusetts. Further south, however, warm winters may allow large numbers of flea beetles to overwinter.

IPM programs in Connecticut and New Jersey recommend 6 beetles per 100 plants as a threshold for control.

Common rust of corn appears as small cinnamon-brown pustules on corn leaves in the late season, especially under cool, humid conditions. Common rust may reduce yield, especially in combination with MDM. Sweet corn cultivars are being developed which have resistance to this rust.

This is perhaps the most conspicuous but least important disease of sweet corn. The smut forms large puffy fruiting bodies which replace corn kernels. In the early stage, the smut is light-colored and edible; it then rapidly darkens and ruptures as the spores are discharged. No control is known, although cultivars vary in their susceptibility.

Sweet corn is a heavy feeder, meaning that the plant needs high levels of nutrients in the soil to support optimal growth. For commercial growers, routine soil testing, usually undertaken in the fall, is the best tool for determining fertility and avoiding nutrient deficiencies. See New England Vegetable Production Recommendations for advice on fertilization.

Trade names are used for identification. No endorsement is implied, nor is discrimination intended against similar materials.

NOTICE: It is unlawful to use any pesticide for other than the registered use. Read and follow the label. User assumes all responsibilities for use inconsistent with the label on the product container.

WARNING: Pesticides are poisonous. Read and follow all directions and safety precautions on labels. Handle carefully and store in original labeled containers, out of reach of children, pets, and livestock. Dispose of empty containers at once, in a safe manner and place. Do not contaminate forage, streams, and ponds.

Issued by Cooperative Extension, E. Bruce MacDougall, Dean, in furtherance of the Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914; University of Massachusetts, United States Department of Agriculture and Massachusetts counties cooperating. AG-335:8/88-2M

Library Lobby | Main Index | Publication List